One thing seared into my mind as a child, was that we were the descendants of slaves, and the land my parents loved, laughed and grew up on, was stained with the blood and pain of our ancestors.

My parents didn't often discuss the historical implications of the slave trade, but it was a subject I thought about endlessly. I used to lie in my bed, eyes closed, and wonder who it was that had been taken from their country. Was it a child – a girl like me? How would she have felt when, crammed onto a ship, she realised she would never see her African homeland again.

Olaudah Equiano and the Slave Trade – that was one of my favourite books. I do not know who the book originally belonged to, whether it was my parents or one of my five brothers, but I do recall the first time I saw it. On the small bookshelf my parents kept in the alcove of their bedroom. Normally the books were elderly hard-covered tomes, with titles such as, "St Peter's Account of His Time in Rome" or "Testament to Friendship" by Vera Brittain, or Bunyan's Pilgrim's Progress, but this book was different.

It was a slim paperback - possibly only 30 pages - and every page was colour. Iimmediately it became my own. This was the only book that told a story like our own, so to me it was a treasure and I read it time and time again throughout my childhood.

Curled up in bed, flowered-eiderdown across my shoulders to keep me warm, I was fascinated as I read the story of how Olaudah and his sister were playing in their village, when slave raiders came and grabbed them. Their arms were tied behind their backs, and then they were marched hundreds of miles away, to the African coast, and finally shipped to the Caribbean to start new lives that were harsh and brutal.

The line “Olaudah never saw his sister again,” was etched on my brain. I read it time and time again. This was Oluadah’s tale, because he found his freedom and became well-known in Britain, but I wondered about the unknown and untold story of his sister.

In my imagination, I was Oludah, and my parent's bed was the ship. I imagined myself, alongside Oludah Equiano - frightened and alone, not knowing or understanding where this ship was heading.

At school, we had a series of books that covered The Tudors, the Stuarts and the Georgians.. Somewhere toward the back of the book, beyond Henry VIII and his various wives, James I and Guy Fawkes, through the Glorious Revolution and Queen Anne, there was a picture that seemed out of place.

It was a ship. A large, sailing ship. Built, my history book told me, in Liverpool, and famous for making voyage after voyage from Africa to the Caribbean.

The illustration, some three hundred years old, showed rows of African slaves crowded together, each occupying a space so small they were unable to move left or right, and forced to sleep in a crouched position for the three months it took the ship to cross the Atlantic Ocean.

I showed the pages to my history teacher. “Miss,” I said, “when will be covering the Caribbean?”

Miss Hargreaves sniffed. She was one of my favourite teachers, but that day she looked uneasy. “I feel.. I feel their histories are too unsettled,” she said eventually. “We won’t be reading those pages.”

I showed the pages to my mother. “Do you know where we are from?” I asked.

She shook her head. “I did not ask my grandma for stories the way that you ask me,” she confessed. “But there is one ancestor I know. Her name was Nanna Manna.”

“Nanna Manna?” Immediately I liked that name. The lyrical quality, how it rolled of the tongue.

“She was my grandmother’s (grand)mother,” my mother told me. “She was born a slave.”

As a slave, Naana Maana was a commodity. A valuable one, but she had not travelled on a slave ship like the one shown in my history book. She had been born in Jamaica, and all her young life she had worked in the fields, or in the house, seen as property to be owned and used by others.

We do not know what she felt, or if she was ever involved in the struggles to end slavery that flared up periodically through the Caribbean at that time. But we know that on 31 July 1834, she went to bed as a slave, and on August 1 the next day, she woke up a free woman, slavery having finally been abolished in the British Caribbean.

“How old was she?” I asked my mum.

“She was young. Not a child, but a very young woman.” Naana Maana would not have been told this, but even as she gained her freedom she was still a commodity, and those who had owned her would have received almost £200 as compensation for her alone – around £7,000 in today’s money.

What Naana Maana did know, was that on the day she gained her freedom she was called to the house by her former owners and given a present.

I was intrigued. A present? A gift from those who owned her? This seemed bizarre to me. My mind could not grasp this. “What did they give her?” I asked. Abit of land so she had a space of her own? A cow or goat so she could raise calves and sell the milk? Or even a bolt of fabric, so she could make herself a nice dress?

"No,” said my mother drily. “None of those things. They gave her a mongoose. In a cage.”

“Oh…” I was not sure what to make of this. “That’s… nice,” I said hesitantly.

“What is nice about a mongoose?” said my mother. I quickly re-arranged my features into a frown. “Do you know what a mongoose is?”

I had read Kipling’s Rikki-Tikki-Tavi during the Christmas holidays and was proud to display my knowledge.

“They look like stoats and eat snakes and rats and stuff, and are friendly and..”

“Friendly!” said my mother. “They are not friendly. They are wild. They called Naanna Maanna to the house and gave her a wild mongoose. In a cage. That was their gift to her. Why?”

I was quiet. Although this had happened over a century before my own mother was born, I sensed that this pained her.

“Why do you think they gave her a mongoose?” my mother said again, but I had no answer.

“What did she do with it?” I asked.

“She looked after it. Took care of it,” my mother shook her head. “I think it was precious to her as she had never received a gift before. She’d feed it in the cage, and talk to it until one day, she looked at it, all caged up, and she felt sorry for it. So she took it outside, just for a moment, she said, to let it have some fresh air and a runaround.”

“And?”

“She opened the cage door, and the mongoose ran straight into the canefields and never came back.”

‘Never?” I said. “Even though Naanna Maana cared for it so much?”

“Never. That was the end of her mongoose. And she never forgot it because she told my grandma about it when she was a little girl.”

It is a small story, and a strange one. Why, out of everything she must have experienced, is that the one that is remembered. And why did the family give her a mongoose in the first place. Something that is wild, that could never be tamed or controlled. A mongoose.

I think those people who had owned Naana Maana were making a point, about the endo f slavery, and what they saw as the loss of their property. Perhaps to them she was their mongoose, she had belonged to them, and she had been set free. And just as it upset my mother, when I think of it, it upsets me.

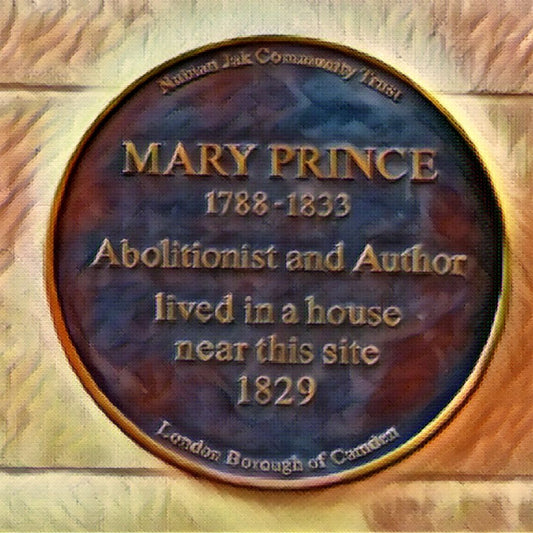

Years later, I saw the illustration of the slave ship once again and learned that it was used by British Quakers as part of their anti-slavery campaign. I learned it had been surveyed in Liverpool, under the directions of the then Prime Minister, WIlliam Pitt. And had been used to show the horrors of the slave trade by the 1788 Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade.

Years later, I saw the illustration of the slave ship once again and learned that it was used by British Quakers as part of their anti-slavery campaign. I learned it had been surveyed in Liverpool, under the directions of the then Prime Minister, WIlliam Pitt. And had been used to show the horrors of the slave trade by the 1788 Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade.

It became the most iconic image of the Atlantic Slave Trade. I had not known these details before.

And there was a further detail I had not seen before, but which now hit me like a sharp crack across the face. For the name of the ship that sailed so often from Africa to the Caribbean, and was the most known ship of the slave trade, was my very own - Brooks.